- The Bowler Estate

- The Celia Green Inn

- Sweetwater Mountain

"Working with Alicia was a pleasure. She certainly listened and took all our ideas to heart. More than that, she turned them into something way beyond our imagination and dreams. She made our home look incredible, simply incredible." - Karen V

Prologue

“30 Years Ago – Here”

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

May 22, 1977

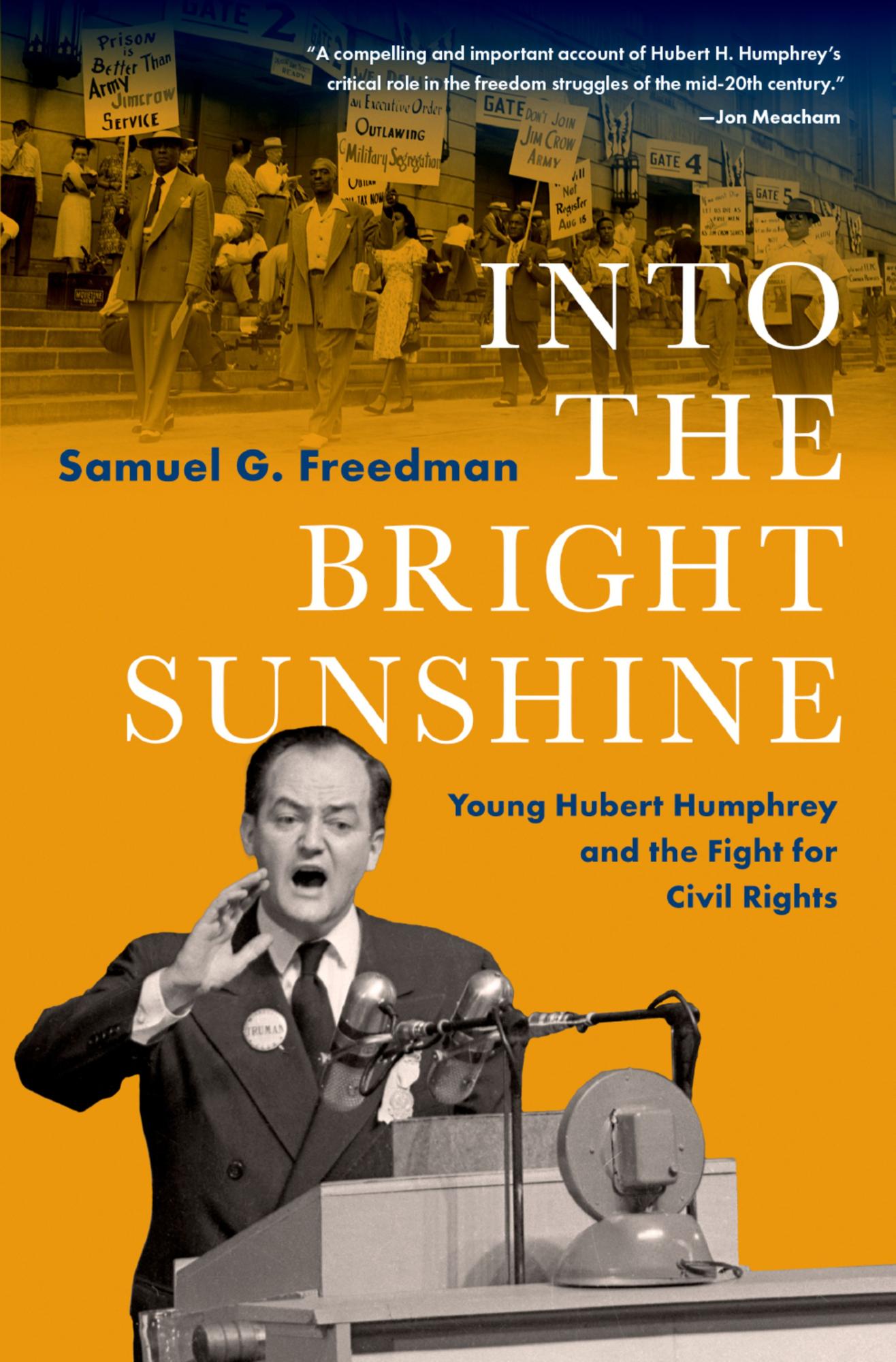

Hubert Humphrey, a fallen hero and a dying man, rose on rickety legs to approach the podium of the Philadelphia Convention Hall, his pulpit for the commencement address at the University of Pennsylvania. He clutched a sheaf of paper with his speech for the occasion, typed and double-spaced by an assistant from his extemporaneous dictation, and then marked up in pencil by Humphrey himself. A note on the first page, circled to draw particular attention, read simply, “30 years ago – Here.”

In this place, at that time, twenty-nine years earlier to be precise, he had made history.

From the dais now, Humphrey beheld five thousand impending graduates, an ebony sea of gowns and mortarboards, broken by one iconoclast in a homemade crown, two in ribboned bonnets, and another whose headgear bore the masking-tape message HI MA PA. In the horseshoe curve of the arena’s double balcony loomed eight thousand parents and siblings, children, and friends. Wearing shirtsleeves and cotton shifts amid the stale heat, they looked like pale confetti from where Humphrey stood, and their flash cameras flickered away, a constellation of pinpricks.

The tableau stirred Humphrey’s memories of the Democratic National Convention on July 14, 1948: the same sweltering air inside the vast hall, the same packed seats and bustling lobby, the same hum of expectancy at the words he was about to utter.

All these years later, Humphrey was standing in very nearly the identical spot.

Since that afternoon in 1948 had placed him on the national stage, Humphrey had assembled credentials more than commensurate with this day’s hortatory role: twenty-three years in the United States Senate, four as vice president to Lyndon Johnson, three times a candidate for his party’s nomination for president, and one very narrow loss as its candidate. In Humphrey’s years as arguably the nation’s preeminent liberal politician, he had pressed for the U.S. and the Soviet Union to negotiate disarmament amid the nuclear standoff of the Cold War, introduced the legislation that created and indeed named the Peace Corps, and helped to floor-manage the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. Relentlessly energetic, effusive to a fault, he practiced what he called “the politics of joy.”

Even so, five days shy of his sixty-sixth birthday, Humphrey was a dynamo diminished. Two cancers were ravaging him, one blighting his body and the other his legacy. As if entwined, each affliction had been inexorably growing over the preceding decade. Nineteen sixty-seven was the year when the escalating war in Vietnam, which Humphrey dutifully supported, deployed nearly half a million American soldiers and took more than ten thousand American lives. It was the year of the “Long Hot Summer,” when Black Americans in more than one hundred fifty cities erupted with uprisings against the police violence and economic inequality that persisted regardless of civil rights laws. And it was the year when Hubert Humphrey first noticed that his urine was stained with blood.

Of the team of doctors who examined Humphrey, only one warned of incipient cancer, and he was overruled. The decision suited Humphrey’s congenital optimism and his yearning for the presidency, and he went through the 1968 campaign assuming good health. The next year, a biopsy confirmed evidence of bladder cancer, and after four more years without Humphrey having either symptoms or treatment, doctors discovered a spot of malignant tissue termed “microinvasive.” The word meant that the rogue cells could sink roots and spread, like the plagues of thistle that overran the wheat fields of Humphrey’s prairie childhood. Subsequent rounds of radiation and chemotherapy, a regimen that Humphrey described as “the worst experience of my life,” bought him three years of remission, and with it the false hope of full recovery.

For in the fall of 1976, Humphrey again spied blood in his urine, and a biopsy confirmed that the bladder cancer, far from defeated, was expanding. Humphrey submitted to the harsh and logical option of having his bladder removed and chemotherapy resumed. For public consumption, wearing a mask of willed buoyancy, Humphrey declared himself fully cured. Newspaper accounts of his stay at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center told of him “prodding patients out of their wheelchairs, shaking hands with everyone in sight and generally infusing gaiety and hope into a normally somber ward.”

In fact, the disease had already invaded Humphrey’s lymph nodes, the staging areas for it to advance with one nearly certain result. On the days when Humphrey received chemotherapy, he was so weak, and perhaps so humiliated, that a young aide had to roll him up into a blanket and carry him between the senator’s car and the Bethesda naval hospital. Humphrey was both impotent and incontinent now, and reduced to relieving himself through a port in his abdomen into a collection bag. In one of the rare moments when private truth slipped out, he described his cancer as “a thief in the night that can stab you in the back.”

The decline of Humphrey’s health coincided with the degradation of his public image. Barely had Humphrey joined Johnson’s White House than the musical satirist Tom Lehrer titled one song on his Top 20 1965 album That Was The Year That Was, “Whatever Became of Hubert?” “Once a fiery liberal spirit,” Lehrer sang in answer to his own question, “Ah, but now when he speaks, he must clear it.” The clearance, Lehrer’s sophisticated listeners understood, had to come from Lyndon Johnson, and its price was Humphrey’s cheerleading for the Vietnam War.

Humphrey received the presidential nomination in 1968 less by competing for it rather than by having it delivered to him by tragic circumstance and machine manipulation: Johnson’s decision in March 1968 not to run for re-election; the assassination in June of the next front-runner, Robert F. Kennedy; and a coronation by the centrist party establishment at a Chicago convention sullied by a police rampage against anti-war protestors. Humphrey campaigned under the twin burdens of an increasingly unpopular war and the televised beating of young activists. At a more personal level, his erstwhile protégé Eugene McCarthy, the Minnesota senator who was revered on the left for his antiwar insurgency against Johnson in the early primaries, withheld his vital endorsement of Humphrey until it was too late to matter.

In defeat, Humphrey returned to the University of Minnesota, his alma mater, where the political science faculty rejected his appointment, ostensibly because he had never finished his doctoral degree. Even after the university managed to place Humphrey in a category of non-traditional faculty, the professors there banned him from their social club, the Thirty-Niners.

When voters returned Humphrey to the U.S. Senate in 1971, it was as a freshman, starting over at the bottom of the seniority totem pole. And when he vied again for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972, he lost to another protégé, George McGovern, the senator from South Dakota whose opposition to the Vietnam War made him an idealistic idol to his youthful legions. Even more humiliating, Humphrey’s trademark ebullience now looked frenetic and desperate. One bard of the counterculture, Hunter S. Thompson of Rolling Stone, laid into Humphrey with particular rhetorical relish. To Thompson’s unsparing eye, Humphrey was “a treacherous, gutless old ward-heeler,” “a hack and a fool,” who “talks like an eighty-year-old woman who just discovered speed.” And in this insult that beyond all others clung in the popular memory, he “campaigned like a rat in heat.”

The calumnies were hardly the exclusive property of Woodstock Nation. Stewart Alsop, a grandee among Washington columnists, reiterated some of Thompson’s barbs in Newsweek. Theodore H. White, American journalism’s authoritative chronicler of presidential campaigns, pronounced that Humphrey “had been part of the scenery too long, as long as Richard Nixon, and had become to the young and the press a political cartoon.”

By the time the 1976 presidential campaign began, Humphrey was sick enough, dispirited enough, or both to stay out of it. His home city of Minneapolis, which he had made a national model of liberalism as mayor, was about to re-elect a law-and-order ex-cop named Charles Stenvig for his third term as mayor in yet one more example of white backlash against racial progress. Another of Humphrey’s protégés, Senator Walter Mondale, vaulted past him into the national spotlight as the incoming vice president for Jimmy Carter. During the week of their inauguration, Humphrey was vomiting from the effects of chemotherapy.

When Congress convened in January 1977, Humphrey tried one last race--running to be Senate Majority Leader. Even his longtime allies in the AFL-CIO let their opposition privately be known because he was “starting to slip fast.” Facing certain defeat, Humphrey withdrew. And the cruelest part of the outcome was assenting to the senator who captured the prize by acclamation. Robert Byrd of West Virginia was a former member of the Ku Klux Klan, a filibustering foe of civil rights legislation, and the very embodiment of the Jim Crow system that Humphrey had devoted his adult life to dismantling.

All of these blows, and the prospect of his own demise, put Humphrey in an uncharacteristically pensive mood – more than just ruminative, closer to depressed. After nearly thirty years in national politics, he found himself wondering what it had all been for.

“I always try to be a man of the present and hopefully of the future,” he wrote in early 1976 to Eugenie Anderson, a career diplomat and longtime friend. “I am, of course, strengthened and inspired by some of the achievements of the yesterdays; but also a person is sobered and tempered by some of the other experiences that didn’t produce such favorable results. I hope the experience that I have had has given me some sense of judgment and a bit of wisdom.”

By January 23, 1977, when Humphrey wrote to Anderson again in the wake of cancer surgery and the failed bid to become majority leader, his tone was even more despairing: “I’m no child and I surely am not naïve, but I do feel that some of those I helped so much might have been a little more loyal. But I suppose it’s part of human weakness so why worry about it. That’s all for now.”

In the present moment, standing before the imminent Penn graduates and their doting families, Humphrey looked visibly weathered, even from a distance. His gown dangled from sloping, bony shoulders as if off a coat hanger. His skin had a grayish hue, the same color as the wispy hair and eyebrows just starting to grow back with the cessation of chemotherapy. His cheeks, the tireless bellows for so many speeches, were shrunken back into the bone. His chin jutted, a promontory.

Even for this celebratory occasion, even on the day he would receive an honorary doctorate, Humphrey was revisiting a place not only of triumph but rebuke. He had been picketed and heckled by anti-war protestors in this very hall in 1965, with one placard asking, “How Much Did You Sell Your Soul For Hubert?” During a presidential campaign rally in Philadelphia in 1968, the signs called him “murderer” and “killer.” And after a speech on the Penn campus during the 1972 primary race against McGovern was disrupted by everything from paper airplanes to chants of “Dump the Hump,” Humphrey lamented, “I’ve been to 192 campuses, but I’ve never had anything like this.”

So as he edged into his commencement address, Humphrey held off from the prepared text, with its survey of international affairs and its appeal for youthful idealism. He led instead with jokes that, depending how one chose to hear them, sounded either self-effacing or self-lacerating. They had the aspect of a perpetual victim mocking himself before any bully could, as if controlling the blow might limit the pain. “I’ve given more speeches than any man ought to be permitted to,” Humphrey said. “I have bored more people over a longer period of time than any man ought to be permitted to.” Then he recalled his own graduation from the University of Minnesota in 1939, and said, “For the life of me, I can’t remember what the commencement speaker said, and I’ll bet you that when you leave here, at least a year from now, you’re gonna say, ‘Who was that fellow? What did he say?’”

Humphrey had the crowd laughing now, not in ridicule, but a kind of affable affinity. Maybe because the Vietnam War was over at last. Maybe because the political villain of the age was Nixon. Maybe because people felt pity for Humphrey’s illness or some pang of conscience about the scorn he had endured. Whatever the reason, Humphrey seized the interval of good will and pivoted into a matter of substance and memory.

“I’ve been reminded…of the day I was here in July nineteen hundred and forty-eight,” he said, his voice reedy and unforced.

“Boy, it was hot, in more ways than one. I was the young mayor of the city of Minneapolis…but in my heart, I had something that I wanted to tell my fellow partisans, and I did.”

What Humphrey said on that day preceded the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery bus boycott led by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the two events commonly and incorrectly understood as the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement. What he said on that day anticipated the wave of civil rights legislation that Lyndon Johnson would push through Congress in the 1960s, addressing the unfinished business of Emancipation. What he said on that day set into motion the partisan realignment that defines American politics right up through the present.

What he said on that day – with Black marchers outside the Convention Hall threatening mass draft resistance against the segregated armed forces, with Southern delegates inside the building vowing mutiny against such equal rights, with the incumbent president and impending nominee, Harry Truman, seething about this upstart mayor’s temerity – followed on two sentences.

“Because of my profound belief that we have a challenging task to do here,” Humphrey had declared from the convention podium, “because good conscience, decent morality demands it, I feel I must rise at this time to support a report, a minority report, a report that spells out our democracy..

“It is a report,” he continued, “on the greatest issue of civil rights.”